On SUBSTACK: The Science of Zen Training—with new updates

A bibliography of research in psychology, neuroscience and leadership

This is a post from my weekly newsletter hosted on Substack . If you like it and would like to get future posts in your inbox, please consider subscribing.

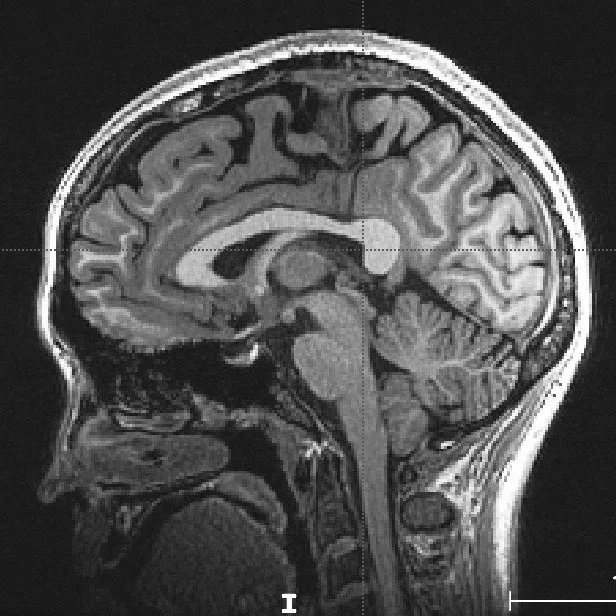

A MRI image of my brain taken during a class on the techniques of neuroscience at Stanford’s medical school.

In October 2019, I published a scientific bibliography of research I think helps explain the characteristics and outcomes of Chozen-ji's approach to Zen training.

At first, I worried that the bibliography would amount to an attempt to "sell" Zen. I didn't intend to try to convince anyone to train in Zen back then and that's still not my intention now. But getting closer to understanding the psychological, physical, and neuroscientific explanations behind what I regularly see at Chozen-ji is really interesting! Or at least it is to me.

Take, for example, the new entry I've added on novice meditators and their heightened sensitivity to pain. We deal with a lot of physical pain at Chozen-ji—sore muscles from hard outside work and martial arts, and stabbing sensations in the knees from long hours of zazen without moving. Now, it's one thing if someone has an actual injury or physical condition. But often, the loudest complaints come from the healthiest people, like former athletes and robust young men. I've often wondered why this might be the case.

In the section of the bibliography on pain, I've added a link and some notes to an online seminar by Dr. Willoughby Britton at Brown University, where she explains the activation of certain regions of the brain during meditation and highlights many negative psychological effects of meditation. In regards to pain, she says that there is a lot of research that shows "somatosensory amplification" during meditation, especially activation of a brain region called the insular cortex.

Some degree of this seems to encompass the good things people want out of meditation, like having more awareness of our physical senses and emotions. Too much, though, seems to create hypersensitivity to physical pain, as well as anxiety and fear—even flashbacks and PTSD. This is fascinating for a few reasons but the practical implication is that whatever meditation is doing to their brain, as opposed to anything happening in their limbs, may be the real cause of that otherwise strong young Zen student's ankle pain as well as their fear of injury.

I have understood ever since I arrived at Chozen-ji that our approach to Zen and Buddhism is totally different from anything else I previously encountered or that may even be available in the West. Now, I'm starting to see how these differences may also lead to different outcomes.

Most meditation research has focused on mindfulness and similar kinds of meditation techniques that “attenuate,” or deprive, the senses, closing the eyes and quieting down one's physical environment in order to push the meditator's awareness inside. This, it turns out, can result in not just meditative insights, but also negative neuropsychological effects like emotional numbing, dissociation, depersonalization (losing a sense of one's self, ownership of one's body or personal items), and social disconnection. Even though they are brought about by meditation, these outcomes strongly resemble or are identical to psychological disorders and it turns out that they are not as uncommon as we think.

However, I do not see them in my experience at Chozen-ji. In many ways, Chozen-ji's approach is the polar opposite to more mainstream kinds of meditation, like mindfulness. Here, we are pushed to pay active attention to everyone and everything outside of us, first. This is especially acute when training in the martial and fine arts. Few things can bring you back into your body or put you in the present moment like hitting someone over the head (and being hit) with a bamboo sword in Kendo, which smarts even when you're wearing protective armor.

Perhaps the martial and fine arts, the lively nature and ubiquitousness of our social interactions, and the cultural values here give us a chance to interrupt and regulate any negative brain states caused by meditation. Maybe this is part of the reason we don't see as many adverse psychological effects of meditation in our population. I try to sum this up in a new section in the bibliography that addresses kiai, or the expression of vital energy (qi or chi in Chinese), and how it informs our training, below.

I know this post is pretty nerdy and assumes deep knowledge of Chozen-ji training or psychology. Thanks for indulging me! I promise to get back to more easily intelligible content next week :-).

Breath

In zazen (seated meditation), the martial and fine arts and beyond, Chozen-ji training focuses on making the breath long, with emphasis on the exhale. The chest does not rise and fall with the breath. Instead, we breathe with the hara, the area of the body wrapping around the abdomen, hips, and buttocks below the belly button. (Edited September 2021.)

Psychology Today, May 9, 2019—Slow breathing and long exhales stimulate your vagus nerve, combat the fight/flight response and regulate Heart Rate Variability.

Biofeedback, Winter 2015—Long term dysfunctional non-abdominal breathing contributes to risk for illness and anxiety. Physical therapy to restore abdominal breathing in post-operative patients reduced these risks.

Posture

In meditation at Chozen-ji, the posture is very upright and active in order to increase one's ki (in Chinese, qi/chi, or vital energy) and facilitate hara breathing. A common instruction is to sit like a mountain or a giant boulder, taking up the whole room. (The rest of the usual instructions will be familiar: push up through the crown of your head, relaxing all the tension in your shoulders.)The eyes are open and you look at a spot 5-10 feet on the floor in front of you, "seeing 180 degrees in every direction"—shorthand for actually seeing, hearing, and feeling everything around you. (Edited September 2021.)

Peper Perspective, July 3, 2018—Correct posture decreased anxiety and improved performance among math test takers.

TEDGlobal 2012, June 2012—Amy Cuddy's "power poses" have largely been debunked, as her results aren't replicable for people of color (go figure). But she was the first psychologist and social scientist to get a lot of attention for talking about the impact of body language on how we feel and see ourselves. (Added September 2021.)

Concentration

At Chozen-ji, concentration is cultivated in zazen by focusing on hara breathing—by observing and manipulating the breath (to make the exhale longer and deeper, and to "set" the air at the top of the inhale), and also by counting each breath. When you've counted 10 breaths, you start counting again from 1, repeating for the duration of the sitting. If you lose count, you start again at one.

Concentration can also be required to maintain posture and seeing 180 degrees. (This section was added in September 2021.)

Mechanisms of Meditation-induced Dissociation: Part 2: Hypoarousal, Britton Lab, Brown University, 2018—Optimal down regulation (i.e., turning down the amount of activation) in a circuit in the brain called the Default Mode Network coinciding with activation in the Prefrontal Cortex can result in increased ability to focus and less "self-referential processing" like self-criticism, mind wandering, and self talk. Many studies show both prefrontal cortex activation and Default Mode Network down regulation as a result of meditation. Too much, though, can impair our ability to interact socially, and to feel empathy and creativity and this has been documented in some people as a negative neuropsychological effect of meditation. (Added September 2021.)

Kiai

Ki in Japanese is the same as chi or qi in Chinese—vital energy. Kiai is how that ki becomes realized (as in, made real). Chozen-ji was the first place I ever heard meditation compared to early man hunting: silent, still, and ready to jump up and kill something! This is accomplished through correct posture, deep hara breathing, and by keeping the eyes and other senses open so as to see 180 degrees.But there is also a general disposition of alertness, readiness, and of having a fighting spirit. (Section added September, 2021.)

Mechanisms of Meditation-induced Dissociation: Part 2: Hypoarousal, 2018—The methods usually used to induce hypoaroused or dissociative and depersonalized states in subjects in a lab strongly resemble the methods of teaching mindfulness and other kinds of meditation. It includes having people do things like stare at a spot on a wall, close their eyes, sit in a very quiet space, and stay still. Depersonalizing language and the present participle are used to describe physical and emotional phenomena: "the foot" instead of "your foot", "noticing the breath" instead of "notice your breathing," and "anger is present" instead of "I feel angry." (Added September, 2021.)

Pain

Meditation at Chozen-ji involves sitting for 45 minutes without moving. If your leg hurts, don't move. If a mosquito lands on your nose, don't move. Combined with muscle soreness from challenging martial arts and outside work, the result is a range of common complaints of physical pain and discomfort—to which the Zen Master may respond, "who's feeling the pain?" (Edited September 2021.)

Mechanisms of Meditation-induced Dissociation: Part 1: Hyperarousal, 2018—Meditation has been shown to stimulate a region of the brain called the insular cortex, which can turn up or turn down the dial on body awareness and emotion regulation. Particularly in novice meditators, too much insula activation can lead to hyperawareness of physical pain, intense emotions, fear, anxiety—even PTSD and flashbacks. (Added September 2021.)

The Routledge Handbook of Philosophy of Pain, 2017—By one definition of the central nervous system, what we know as pain is actually the product of two parallel systems in the brain or neuromatrices. The first processes potentially harmful stimuli, called noxious sensation. But it's only the second that then codes this perceived sensation as "pain".

Journal of Neuroscience, 2019—Sleep loss heightens one's awareness of noxious sensation—what we usually identify as pain—and lowers the threshold for pain.

Psychology Today, April 19, 2012—Emotional and physical pain are experienced in similar regions of the brain—again, the insular cortex (and the anterior cingulate cortex). I'm waiting for a study testing whether a kind of exposure therapy with physical pain can be effective in addressing our responses to emotional pain and mental distress.

Brain and Behavior, 2016—Meditation training like that taught in Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction increases the intensity of sadness in meditators. (Added September 2021.)

Neuroimage, August 15, 2011—Intensity of positive and negative emotions is decreased by meditation, leading to greater emotional stability. (Added September 2021.)

Practical anti-individualism

There are strong hierarchies and very detailed forms in Zen training. A big part of the training is thus learning to pay attention, follow, and match—a contrast with the values of individual freedom, expression, and choice. This, combined with the value of helping others before ourselves, is a practical means to explore what it means to be a bodhisattva committed to the liberation of all beings from suffering, not just one's own enlightenment. (Section title and description revised September 2021.)

Harvard Business Review, August 6, 2018—It may be that the most effective leaders are not the ones who seek to individuate themselves, seeing themselves as natural leaders and standing apart from their group. Instead, believing oneself to be a good follower and endeavoring to be a good member of a group may be the best marker for an effective leader. "People will be more effective leaders when their behaviors indicate that they are one of us, because they share our values, concerns and experiences, and are doing it for us, by looking to advance the interests of the group rather than own personal interests."

Emotion, 2016—Focusing on yourself and typical "self care" behaviors—even enjoying a personal hobby or a favorite meal—don't make you happier. What does, though, is "prosocial behavior" or any act that focuses on benefiting another person. Doing these result in greater and lasting feelings of joy, contentment and love, and fewer negative emotions. In contrast, self-focused behavior shows no impact on either positive or negative emotions.